The Gut as a Second Brain: What the Latest Research Reveals About the Mind in Your Belly

Michael Donovan, PhD

12/5/20257 min read

For centuries, we've understood the brain as the sole command center of human consciousness, emotion, and cognition. But groundbreaking research over the past decade has revealed something extraordinary: nestled within the walls of our digestive system lies a complex neural network so sophisticated that scientists now call it our "second brain." This discovery is revolutionizing our understanding of mental health, immunity, and overall wellbeing.

The Enteric Nervous System: A Brain in Your Gut

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is an extensive mesh of neurons embedded in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract, stretching from the esophagus to the rectum. With approximately 500 million neurons—more than in the spinal cord—this system operates with remarkable autonomy, capable of functioning independently from the brain in our skull.

Unlike other organs that simply follow orders from the central nervous system, the gut makes its own decisions. It can sense nutrients, detect pathogens, coordinate muscle contractions for digestion, and regulate blood flow—all without consulting the brain. This independence is why you can digest food even when unconscious or when your spinal cord is severed.

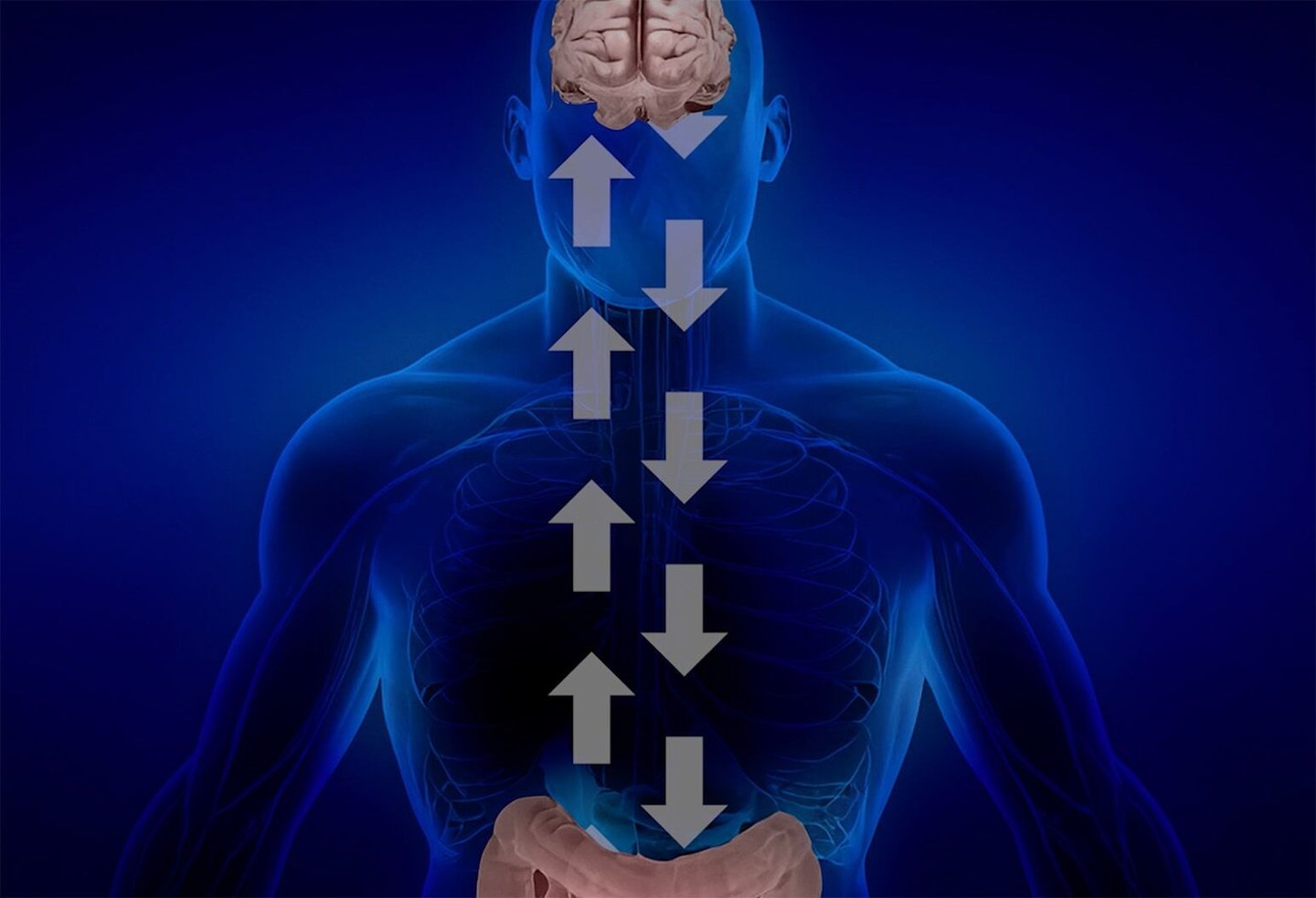

But the relationship between these two "brains" is far from disconnected. They communicate constantly through a superhighway of signals called the gut-brain axis, exchanging information that profoundly influences our mental state, immune function, and physical health.

The Microbiome: Trillions of Tiny Influencers

Recent research has revealed that the gut's influence extends far beyond its neural network. Our digestive tract hosts approximately 100 trillion microorganisms—bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes—collectively known as the gut microbiome. These microscopic residents outnumber our own cells and contain genes that vastly outnumber our human genome.

These microbes aren't passive passengers. They produce neurotransmitters, synthesize vitamins, train our immune system, and manufacture metabolites that can cross the blood-brain barrier to directly affect brain function. Studies have shown that gut bacteria produce substantial amounts of serotonin, dopamine, and GABA—the same neurochemicals that regulate our mood, motivation, and anxiety levels.

The composition of this microbial community varies dramatically between individuals and can be influenced by diet, stress, medications, and environmental factors. This variability helps explain why people respond differently to the same foods, medications, and stressors.

Depression and Anxiety: Looking to the Gut for Answers

One of the most compelling areas of gut-brain research involves mental health. Multiple studies have found distinct differences in the gut microbiome of people with depression and anxiety compared to healthy individuals. These findings have sparked a new hypothesis: could some forms of mental illness originate in the gut?

Research using animal models has provided striking evidence. When scientists transfer gut bacteria from depressed humans to germ-free mice, those mice begin exhibiting behaviors consistent with depression and anxiety. Conversely, introducing beneficial bacterial strains can reduce anxious behaviors and improve stress resilience.

Human studies are yielding promising results as well. Clinical trials testing specific probiotic strains—sometimes called "psychobiotics"—have shown improvements in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. While these interventions don't replace traditional treatments, they suggest that supporting gut health could become a valuable component of mental health care.

The mechanisms behind these effects are still being unraveled, but research suggests multiple pathways. Gut bacteria influence inflammation throughout the body, including in the brain, and chronic inflammation has been linked to depression. They also affect the production of neurotrophic factors that support neuron growth and plasticity. Additionally, the vagus nerve, which connects the gut to the brain, appears to transmit microbial signals that alter brain chemistry and activity.

The Gut's Role in Neurodegenerative Disease

Perhaps the most surprising frontier in gut-brain research involves neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson's disease. Researchers have discovered that Parkinson's may actually begin in the gut, decades before motor symptoms appear in the brain.

Studies have found abnormal protein aggregates—the hallmark of Parkinson's—in the gut nervous system of patients years before their diagnosis. Some research suggests these proteins may travel from the gut to the brain via the vagus nerve, spreading in a prion-like fashion. This discovery has opened new avenues for early detection and intervention.

Alzheimer's disease research is also pointing toward the gut. The microbiome composition differs significantly between Alzheimer's patients and healthy individuals, and certain bacterial metabolites have been found to either promote or protect against the brain changes characteristic of the disease. Some researchers are now investigating whether modifying the gut environment could slow cognitive decline.

Autism and the Gut Connection

Many individuals with autism spectrum disorder experience severe gastrointestinal problems, a connection that has long puzzled researchers and families. Recent studies suggest this isn't coincidental—the gut microbiome may play a role in autism's development and symptoms.

Children with autism show distinct microbial signatures in their gut, with reduced diversity and altered proportions of certain bacterial species. Remarkably, small pilot studies using fecal microbiota transplants (transferring healthy gut bacteria from donors) have shown improvements not only in digestive symptoms but also in autism-related behaviors.

While this research is still in early stages and such treatments remain experimental, it suggests that the gut-brain connection may be particularly critical during neurodevelopment. The mechanisms appear to involve how gut microbes influence immune system maturation, inflammation, and the production of metabolites that affect brain development.

Food, Mood, and the Gut-Brain Axis

The ancient wisdom that "you are what you eat" is being validated through modern neuroscience, but the story is more complex than previously imagined. Diet doesn't just affect our physical health—it shapes our brain function through its impact on gut microbes.

High-fiber diets promote beneficial bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids, compounds with anti-inflammatory properties that can enhance brain function and mood. The Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables, fermented foods, and omega-3 fatty acids, has been associated with reduced depression risk—effects that may be mediated partly through the gut.

Conversely, diets high in processed foods, sugar, and unhealthy fats can promote harmful bacterial overgrowth and intestinal inflammation. This may explain why such diets are associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety, beyond their metabolic effects.

Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, kimchi, and sauerkraut introduce beneficial bacteria directly, while prebiotic fibers feed the good microbes already present. Research suggests that regularly consuming these foods may support both digestive and mental health.

Stress: The Gut's Greatest Enemy

The gut-brain connection is bidirectional, and stress vividly illustrates this two-way street. When we experience psychological stress, our gut responds with altered motility, increased permeability (often called "leaky gut"), and changes in microbial composition. These changes, in turn, can amplify stress responses and mood disturbances, creating a vicious cycle.

Chronic stress can reduce microbial diversity and promote the growth of harmful bacteria while suppressing beneficial species. This disruption affects the production of mood-regulating neurotransmitters and increases inflammatory signaling throughout the body and brain.

Understanding this connection has practical implications. Stress management techniques—meditation, exercise, adequate sleep—don't just calm the mind; they protect gut health. Similarly, supporting gut health through diet and probiotics may enhance our resilience to stress.

The Immune System's Role

The gut-brain-immune axis forms a complex triangle of communication. Approximately 70% of our immune system resides in and around the gut, constantly sampling the microbial environment and responding to threats. The gut microbiome essentially trains this immune tissue, teaching it to distinguish friends from foes.

When this balance is disrupted—a condition called dysbiosis—the immune system can become overactive, triggering chronic inflammation. This inflammation doesn't stay confined to the gut; inflammatory molecules and activated immune cells can reach the brain, where they've been implicated in depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline.

This immune connection helps explain why inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn's and ulcerative colitis are associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety. It also suggests new treatment approaches: reducing gut inflammation may alleviate mental health symptoms, while addressing systemic inflammation might improve both gut and brain health.

Practical Applications: From Research to Reality

While gut-brain research is still evolving, several practical strategies have emerged for supporting this vital connection:

Diversify your diet: A varied, plant-rich diet promotes microbial diversity. Aim for 30 different plant foods per week, including vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, and whole grains.

Include fermented foods: Regular consumption of yogurt, kefir, kimchi, sauerkraut, or kombucha can introduce beneficial bacteria. Start small if you're not accustomed to these foods.

Feed your microbes: Prebiotic fibers from foods like onions, garlic, leeks, asparagus, bananas, and oats nourish beneficial bacteria.

Limit processed foods: Ultra-processed foods, artificial sweeteners, and emulsifiers can harm gut microbes and increase intestinal permeability.

Manage stress: Regular meditation, exercise, and adequate sleep protect gut health and support beneficial microbial communities.

Be cautious with antibiotics: While sometimes necessary, antibiotics can significantly disrupt gut microbiomes. Use them judiciously and consider probiotic supplementation during and after treatment.

Consider probiotics thoughtfully: Not all probiotics are equal, and effects are strain-specific. For mental health, look for research-backed psychobiotic strains like Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium longum.

The Future of Gut-Brain Medicine

The therapeutic potential of the gut-brain axis is immense and largely untapped. Researchers are developing sophisticated approaches including:

Precision probiotics: Designer bacterial strains engineered to produce specific therapeutic compounds or colonize particular gut regions.

Postbiotics: Rather than live bacteria, these treatments use beneficial bacterial products—metabolites, proteins, or cell wall components—that may be more stable and targeted.

Microbial biomarkers: Tests that analyze gut microbiome composition to predict disease risk, personalize treatments, or monitor therapeutic responses.

Vagus nerve stimulation: Non-invasive techniques to enhance communication between gut and brain, potentially treating depression, inflammation, and digestive disorders.

Dietary psychiatry: Emerging as a legitimate medical field, integrating nutritional interventions into mental health treatment protocols.

Challenges and Cautions

Despite the excitement surrounding gut-brain research, important limitations remain. Much of the mechanistic work has been conducted in animals, and human studies are often small or preliminary. The microbiome varies dramatically between individuals, making universal recommendations challenging.

The probiotic industry, while growing rapidly, remains poorly regulated. Many products lack evidence of efficacy, contain insufficient bacterial quantities, or don't survive passage through stomach acid. Claims often outpace science.

Additionally, our understanding of which specific bacterial strains do what, and how they interact with each other and with our own cells, is still rudimentary. The microbiome represents an ecosystem of staggering complexity, and simplistic interventions may not yield expected results.

Conclusion: Trusting Your Gut Takes on New Meaning

The discovery of the gut as a second brain represents a paradigm shift in medicine and neuroscience. This revelation challenges the notion that our mental and emotional lives are solely products of the brain in our skull, revealing instead that consciousness and wellbeing emerge from a dialogue between multiple body systems.

We're learning that caring for our gut through diet, stress management, and thoughtful use of medications isn't just about digestive comfort—it's about supporting our mental clarity, emotional stability, and long-term brain health. The phrase "trust your gut" takes on new scientific validity when we understand that the gut is literally communicating with our brain, influencing our decisions, moods, and perceptions.

As research accelerates, we can expect revolutionary changes in how we prevent and treat mental illness, neurodegenerative disease, and even conditions we don't yet recognize as gut-related. The future of medicine will increasingly recognize that healing the mind requires healing the gut, and vice versa.

Our two brains—one in our head, one in our belly—evolved to work in harmony. By honoring this connection and supporting both, we open new pathways to health that our ancestors intuitively understood but that modern science is only now beginning to fully appreciate.