The Dunning-Kruger Effect in Health, Wellness & Fitness: Why a Little Knowledge Can Be Dangerous

Michael Donovan, PhD

11/3/202514 min read

We've all encountered them at the gym: the person who started lifting weights three months ago and is now dispensing unsolicited advice about muscle hypertrophy and periodization. Or perhaps the newly-minted yoga enthusiast who insists their limited understanding of Ayurveda can cure chronic illness. These scenarios perfectly illustrate one of psychology's most fascinating phenomena—the Dunning-Kruger effect—and nowhere does it manifest more visibly or potentially dangerously than in the realm of health, wellness, and fitness.

Understanding the Dunning-Kruger Effect

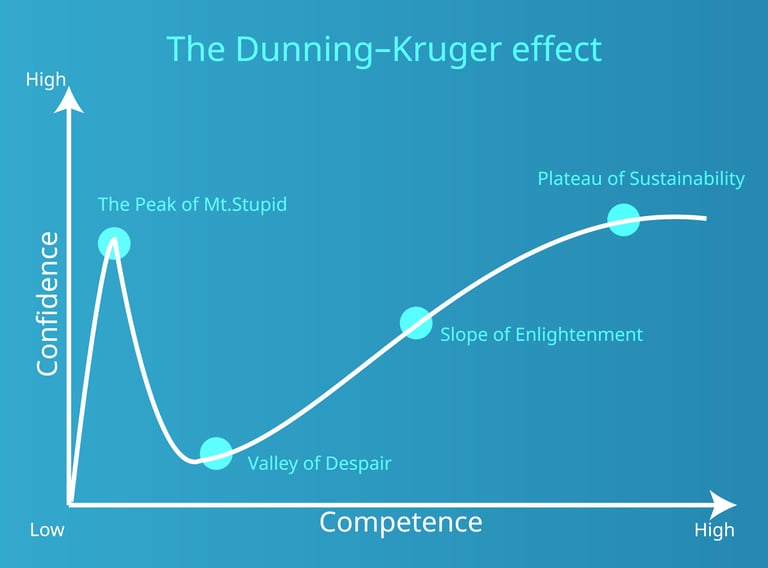

The Dunning-Kruger effect, named after psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger who published their seminal research in 1999, describes a cognitive bias in which people with limited knowledge or competence in a domain overestimate their own ability. Conversely, experts often underestimate their competence, assuming that what comes easily to them is equally obvious to others.

The original study found that individuals who scored in the bottom quartile on tests of humor, grammar, and logic grossly overestimated their performance. More importantly, they lacked the metacognitive ability to recognize their incompetence. In other words, they didn't know enough to know what they didn't know.

This creates a dangerous paradox: the less someone knows about a subject, the more confident they may feel about their understanding of it. In health and fitness, where the stakes involve our physical wellbeing and potentially our lives, this cognitive bias can lead to consequences ranging from ineffective training programs to serious injury or illness.

The Peak of Mount Stupid

In fitness and health communities, there's an informal term for the early stage of the Dunning-Kruger curve: "Mount Stupid." This represents the peak confidence that occurs shortly after someone begins learning about fitness or nutrition. They've absorbed enough information to feel knowledgeable but haven't encountered enough complexity to understand the limitations of their knowledge.

Consider the typical journey of someone new to fitness. After reading a few articles about macronutrients and watching some YouTube videos about compound lifts, they feel equipped to design comprehensive training programs and nutritional protocols. They've learned that protein builds muscle, so they assume more protein is always better. They've discovered that squats are the "king of exercises," so they program squats every day. They've read that carbs spike insulin, so they declare all carbohydrates evil.

This oversimplification is characteristic of Mount Stupid. The nuances—individual differences in protein synthesis, the importance of recovery and periodization, the context-dependent nature of nutrition—remain invisible to them. Yet their confidence is sky-high because they've experienced the rush of initial learning without yet encountering the vast territory of unknown unknowns.

The Valley of Despair and Beyond

As people continue their fitness journey and education, most eventually descend into what's colloquially called the "Valley of Despair." This is the phase where they begin to recognize how much they don't know. They discover that exercise science is complex, that individual responses to training vary enormously, that nutrition research is full of contradictions and context-dependencies, and that the human body is remarkably complex and adaptive.

The person who once confidently proclaimed "just do keto" begins to understand the nuances of metabolic flexibility, the role of gut microbiome in carbohydrate tolerance, the importance of dietary adherence over theoretical optimality, and the psychological factors in eating behavior. Their confidence drops not because they know less, but because they're finally beginning to grasp the true scope of the domain.

Those who persist eventually reach the "slope of enlightenment" and finally the "plateau of sustainability"—a place where knowledge and confidence come into appropriate alignment. These are your experienced coaches who preface advice with questions about context, your educated fitness enthusiasts who respond to questions with "it depends," and your knowledgeable nutritionists who recognize that theoretical optimality often bows to practical adherence.

Manifestations in the Fitness Industry

The fitness industry is particularly susceptible to Dunning-Kruger effects for several reasons. First, the barrier to entry is remarkably low. Anyone can create a social media account and begin dispensing fitness advice without credentials, oversight, or accountability. Second, fitness has a powerful just-world appeal—visible results create the perception of expertise, even when those results came from favorable genetics, performance-enhancing drugs, or simply youth rather than from the methods being promoted.

The Certified Personal Trainer with 40 Hours of Education

Consider the newly certified personal trainer. Most basic personal training certifications require somewhere between 40 and 150 hours of study. This is enough to learn fundamental movement patterns, basic program design, and general safety protocols. It is not enough to understand exercise physiology, biomechanics, program periodization, special populations, pain science, or the countless other domains relevant to training diverse clients effectively.

Yet many new trainers emerge from certification with supreme confidence in their abilities. They've just learned about the stretch-shortening cycle, so they program plyometrics for everyone. They've discovered that "functional training" exists, so they put every client on a BOSU ball. They learned one cueing technique that worked for them, so they apply it universally.

The most dangerous manifestation occurs when these trainers encounter clients with complex medical histories, movement limitations, or pain. A trainer on Mount Stupid may confidently prescribe exercises that exacerbate underlying conditions, may dismiss legitimate pain as "mental weakness," or may push through obvious compensation patterns that lead to injury. An experienced trainer recognizes these scenarios as immediate red flags requiring medical referral or extensive modification.

The Internet Fitness Guru

Social media has democratized information sharing, which has both benefits and significant drawbacks. The algorithm rewards confidence, boldness, and simplicity. Nuanced takes like "it depends on your goals, current fitness level, injury history, and preferences" don't generate engagement. Absolute declarations like "THIS EXERCISE IS KILLING YOUR GAINS" or "THE ONLY DIET THAT WORKS" do.

This creates a perverse incentive structure that actively rewards Dunning-Kruger behavior. The fitness influencer who has been training for two years and thinks they've figured out the "secret" to muscle growth receives more engagement than the exercise science PhD who carefully explains the current state of hypertrophy research, its limitations, and individual variability.

The result is a landscape where confidence is mistaken for competence, where certainty is more valued than accuracy, and where the most visible voices are often the least qualified. The person seeking fitness information cannot easily distinguish between the overconfident novice and the genuine expert, especially when both present their information with equal conviction.

The CrossFit/HIIT/Boutique Fitness Enthusiast

Specialized fitness communities often create echo chambers that amplify Dunning-Kruger effects. Someone who finds success with a particular training modality—whether CrossFit, HIIT, powerlifting, yoga, or any other approach—may begin to view it as the optimal approach for everyone.

The newly converted CrossFitter who finally found a form of exercise they enjoy may begin to dismiss all other training methods as inferior. They've experienced the benefits of varied functional movements and high-intensity training, but they haven't yet recognized that this modality worked for them in their context with their goals, preferences, and body. They haven't yet encountered the limitations—the repetitive strain injuries common in high-volume Olympic lifting, the inadequacy for pure strength or hypertrophy goals, or the inappropriateness for many special populations.

This isn't to critique any particular training methodology. Every approach has merits and limitations. The Dunning-Kruger effect manifests when practitioners lack the experience to recognize these boundaries and instead make absolute claims about superiority.

Nutritional Nonsense and Dietary Dogma

If the fitness world is susceptible to Dunning-Kruger effects, the nutrition world is a breeding ground for them. Nutrition science is notoriously complex, full of confounding variables, individual differences, and contradictory studies. This complexity creates fertile ground for oversimplified certainty.

The Reformed Eater

One of the most common manifestations occurs when someone discovers a dietary approach that works for them personally. Perhaps they tried intermittent fasting and lost 20 pounds. Or they eliminated gluten and their digestive issues resolved. Or they started counting macros and finally achieved the physique they wanted.

The psychological impact of this transformation can be profound. After struggling for years, they finally found something that worked. The natural human tendency is to attribute this success to the specific methodology rather than to the combination of factors that actually produced the result—increased dietary awareness, caloric deficit, elimination of personally problematic foods, or simply the motivation that comes with novelty.

This person then ascends Mount Stupid in nutrition, declaring that their approach is "the answer." The intermittent faster insists that meal timing is the key to fat loss, dismissing the role of overall caloric balance. The gluten-avoider becomes convinced that gluten is universally toxic, not recognizing that their personal intolerance isn't universal. The macro tracker can't understand why someone wouldn't want to weigh and measure every meal, blind to the psychological burden this places on some individuals.

The Supplement Salesperson

The supplement industry is perhaps the ultimate expression of nutritional Dunning-Kruger. Multi-level marketing companies recruit distributors with minimal training and arm them with exaggerated claims about their products. These distributors, many of whom have no background in nutrition, biochemistry, or physiology, then confidently declare that their shake will "detoxify your cells," their supplements will "activate your metabolism," or their proprietary blend will "optimize your hormones."

The confidence comes from a combination of factors: a brief training period that teaches just enough to sound knowledgeable, cherry-picked research that supports product claims, anecdotal success stories that create the illusion of effectiveness, and financial incentives that discourage critical thinking. The result is an army of confidently incompetent nutrition advisors making claims that range from exaggerated to dangerous.

The Documentary Convert

Netflix and other streaming platforms have given us a new phenomenon: the documentary convert. Someone watches a compelling documentary about plant-based eating, ketogenic diets, or the dangers of sugar, and emerges convinced they've discovered nutritional truth. The documentary's narrative arc, emotional appeals, and selective presentation of evidence create powerful conviction.

The problem is that documentaries are entertainment, not education. They're designed to tell a compelling story, not to present balanced evidence. The person who watches "What the Health" doesn't receive a comprehensive review of nutritional science—they receive a one-sided presentation designed to convince them of a particular viewpoint. Yet they emerge with the confidence of someone who has deeply studied the subject.

This person then begins sharing nutritional advice based on their single-source "education." They confidently declare that meat causes cancer, that fats make you fat, that you must eat breakfast to "jumpstart your metabolism," or any other number of claims that misrepresent or oversimplify complex science. Their confidence is indistinguishable from expertise, but the foundation is simply a well-crafted narrative.

The Dangers: Why This Matters

One might argue that misplaced confidence in fitness and nutrition is relatively harmless—after all, how much damage can someone really do with a suboptimal workout program or imperfect diet? Unfortunately, the answer is: quite a lot.

Physical Injury

Overconfident advice regularly leads to injury. The trainer who doesn't recognize contraindications pushes a client into an exercise that aggravates an existing condition. The gym bro who insists that everyone must do heavy deadlifts creates back injuries in people who lack the mobility or stability for safe execution. The HIIT enthusiast who ignores the warning signs of overtraining winds up with chronic injuries or rhabdomyolysis.

The progression is tragically common: a person with insufficient knowledge confidently prescribes an approach, the recipient trusts that confidence as a proxy for competence, an injury occurs, and the overconfident advisor either blames the victim for "doing it wrong" or doubles down on their approach. Meanwhile, the injured person has learned to distrust fitness advice entirely.

Disordered Eating and Body Image Issues

Nutritional Dunning-Kruger can be even more insidious. Confident but incorrect nutritional advice frequently contributes to disordered eating patterns and unhealthy relationships with food. The influencer who insists on eliminating entire food groups creates unnecessary restrictions that can evolve into orthorexia. The trainer who mandates strict macros and daily weigh-ins may not recognize the signs of developing eating disorders in susceptible individuals.

The "wellness" industry has become particularly problematic in this regard. People with no training in nutrition or psychology confidently prescribe restrictive diets, detoxes, and cleanses while dismissing legitimate concerns as "detox symptoms" or "healing crises." They've climbed Mount Stupid and now dispense advice that can trigger or exacerbate eating disorders, nutritional deficiencies, and psychological distress around food.

Delayed Medical Treatment

Perhaps most dangerously, overconfident health and wellness advisors sometimes discourage people from seeking proper medical care. The nutritionist who insists supplements can cure diabetes may delay insulin therapy. The chiropractor who claims they can treat any condition through spinal manipulation may prevent necessary medical workups. The wellness coach who attributes serious symptoms to "toxins" or "inflammation" may miss genuine medical emergencies.

These scenarios represent the darkest manifestation of the Dunning-Kruger effect. The advisor lacks the knowledge to recognize the boundaries of their competence, the client trusts their confidence as expertise, and serious medical conditions go unaddressed until they reach crisis points.

Why Health and Fitness Attract Dunning-Kruger

Several factors make health and fitness particularly susceptible to this cognitive bias:

Apparent Simplicity: Exercise and nutrition seem intuitively simple. Lift weights, eat less, move more—how complicated could it be? This apparent simplicity masks enormous underlying complexity, creating the perfect conditions for overconfidence.

Personal Experience as Evidence: Everyone has a body and everyone eats, which creates the illusion that personal experience translates to general expertise. "This worked for me" becomes "this is the right approach," without recognizing the role of individual differences, context, genetics, and countless other variables.

Visible Results: Unlike many domains where competence is abstract, fitness produces visible results. The person who builds an impressive physique is assumed to be knowledgeable about training and nutrition, even if their results came from factors other than the methods they promote. This creates a halo effect where physique is mistaken for knowledge.

Low Barrier to Entry: Anyone can become a trainer, coach, or wellness advisor with minimal training. Unlike medicine or law, which have rigorous educational requirements and licensure, fitness and nutrition advice can be dispensed by anyone with a certification that required a weekend course.

Commercial Incentives: The fitness and wellness industries are extremely lucrative. This creates financial incentives to overstate competence, make exaggerated claims, and present oneself as more expert than one actually is. Confidence sells; uncertainty doesn't.

Complexity and Contradictions: Genuine nutrition and exercise science is full of nuance, individual variation, and apparent contradictions. This complexity makes it easier for people with superficial knowledge to cherry-pick evidence that supports their preferred narrative while ignoring contradictory findings.

Recognizing Dunning-Kruger in Others (and Yourself)

How can you identify when someone (including yourself) might be on Mount Stupid? Several red flags suggest overconfidence relative to competence:

Absolute Statements: Be wary of anyone who speaks in absolutes. "This diet is the only way to lose fat." "This exercise is worthless." "Everyone should do this." Genuine experts recognize individual variation and context-dependence. They say "it depends" more than "definitely."

Single-Cause Explanations: Health and fitness are multifactorial. When someone attributes results to a single factor while ignoring others, it suggests oversimplification. "I lost weight because I stopped eating after 6pm" ignores the caloric deficit that intermittent fasting created. "I built muscle because of this supplement" ignores the training, sleep, and nutrition that actually drove adaptation.

Dismissal of Alternative Approaches: If someone insists their method is superior while dismissing all alternatives, they likely haven't explored those alternatives thoroughly enough to understand their merits and limitations. Experienced practitioners recognize that many approaches can work and that optimality depends on context.

Overemphasis on Anecdote: Personal success stories are powerful but don't constitute evidence of general effectiveness. When someone relies primarily on "this is what worked for me" without understanding why it worked or for whom else it might work, they're operating from limited knowledge.

Resistance to Questions: Genuine experts welcome questions and challenges—they're an opportunity to teach and to refine understanding. People on Mount Stupid become defensive when questioned because they lack the depth of knowledge to address challenges confidently.

Recently Discovered Knowledge: Be particularly cautious of advice from people who recently learned something and are now teaching it enthusiastically. The person who discovered powerlifting six months ago is likely still on Mount Stupid, regardless of how confident they seem.

Lack of Nuance: If advice comes without conditions, caveats, or individual considerations, it's likely oversimplified. "What's the best exercise for glutes?" "Hip thrusts." This answer ignores individual anatomy, training history, equipment access, preferences, and countless other relevant factors.

Navigating the Landscape: Finding Genuine Expertise

Given the prevalence of Dunning-Kruger effects in fitness and wellness, how can someone seeking information distinguish genuine expertise from overconfident ignorance?

Look for Appropriate Uncertainty: Paradoxically, genuine experts are often less certain than overconfident novices. They recognize the complexity of their domain and the limitations of current knowledge. They use phrases like "evidence suggests," "in this context," "it depends on," and "we're not entirely sure yet."

Check Credentials Carefully: While credentials aren't everything, they do indicate a baseline level of education. Look for advanced degrees in relevant fields (exercise physiology, nutrition science, kinesiology), not just weekend certifications. Be particularly skeptical of self-created titles like "health coach" or "wellness expert" that have no regulated meaning.

Evaluate Scope of Practice: Genuine professionals recognize the boundaries of their expertise. A personal trainer should acknowledge when a client needs medical evaluation. A nutritionist should recognize when eating behaviors indicate psychological issues requiring therapy. Someone who claims to be able to address everything from depression to autoimmune disease through diet and exercise is vastly overestimating their competence.

Seek Evidence-Based Practice: Does this person reference research? Do they update their views when new evidence emerges? Do they acknowledge when research is limited or contradictory? Be skeptical of anyone who can't cite sources or who dismisses research as irrelevant to practical application.

Value Experience with Diverse Populations: The trainer who has only worked with healthy young adults has limited perspective compared to one who has trained elderly clients, individuals with chronic conditions, pre/postnatal populations, and athletes across different sports. Breadth of experience builds genuine expertise and reveals the limitations of one-size-fits-all approaches.

Notice How They Handle Disagreement: Genuine experts can engage with disagreement productively. They can acknowledge merit in opposing viewpoints and explain their reasoning without becoming defensive. They change their minds when presented with compelling evidence.

Escaping Your Own Mount Stupid

If you're involved in fitness and wellness—whether as a professional or an enthusiast—how can you avoid falling prey to the Dunning-Kruger effect yourself?

Cultivate Intellectual Humility: Recognize that your current knowledge is incomplete and always will be. The more you learn, the more you should recognize how much remains unknown. If you feel absolutely certain about complex issues, you probably don't understand them well enough yet.

Seek Diverse Perspectives: Deliberately expose yourself to viewpoints that challenge your current understanding. If you're convinced that low-carb is optimal, study the arguments for high-carb performance. If you believe in high-frequency training, understand the rationale for low-frequency approaches. This doesn't mean abandoning your views, but it does mean understanding the legitimate complexity of the field.

Study the Research (Properly): Don't just read abstracts or cherry-pick studies that support your preferred conclusions. Understand research methodology well enough to evaluate study quality. Learn to identify limitations. Recognize that individual studies don't prove anything—you need to evaluate the broader body of evidence.

Collect Data on Yourself: If you're giving advice based on "what worked for you," make sure you actually know what worked. Track variables, recognize confounding factors, and acknowledge uncertainty. "I lost fat while intermittent fasting" is different from "I lost fat because of intermittent fasting," and both are different from "therefore intermittent fasting is optimal for fat loss."

Maintain Scope of Practice: If you're a personal trainer, train people. Don't diagnose injuries, prescribe specific diets for medical conditions, or claim to cure disease through exercise. Recognize the boundaries of your competence and refer out appropriately.

Never Stop Learning: View your education as ongoing. Attend conferences, take advanced courses, read current research, and maintain curiosity. The moment you believe you've figured everything out is the moment you've stopped learning and probably climbed Mount Stupid.

Value Questions Over Answers: Develop comfort with "I don't know." The ability to say "that's a great question, and I'd need to research that further" or "there's legitimate debate on that topic" is a sign of genuine expertise, not weakness.

Conclusion: The Wisdom of Knowing What You Don't Know

Socrates famously claimed that his wisdom consisted in knowing that he knew nothing. While that may be an overstatement, the principle remains valuable: genuine knowledge includes recognition of the boundaries of that knowledge.

In health, wellness, and fitness, the Dunning-Kruger effect creates a paradox where the least knowledgeable are often the most confident, while genuine experts are appropriately humble about the limitations of their understanding. This creates a landscape where bad advice is often delivered more confidently than good advice, where simplicity is mistaken for clarity, and where certainty is valued over accuracy.

The solution isn't to distrust all advice or to demand PhD-level credentials from your personal trainer. Rather, it's to develop the discernment to distinguish confident ignorance from genuine expertise. Look for appropriate uncertainty, respect for complexity, acknowledgment of individual differences, and intellectual humility. Be skeptical of absolute claims, one-size-fits-all solutions, and anyone who claims to have all the answers.

If you're in the position of giving advice—whether as a professional or simply as an enthusiastic friend—remember that confidence isn't the same as competence. The more certain you feel, the more you should question whether you truly understand the complexity of what you're addressing. The ability to say "it depends," "I'm not sure," or "that's outside my expertise" isn't a weakness—it's a sign that you've descended from Mount Stupid and begun the real journey toward genuine understanding.

Your future clients, friends, and your own body will thank you for it.